Image Generated Using 4o

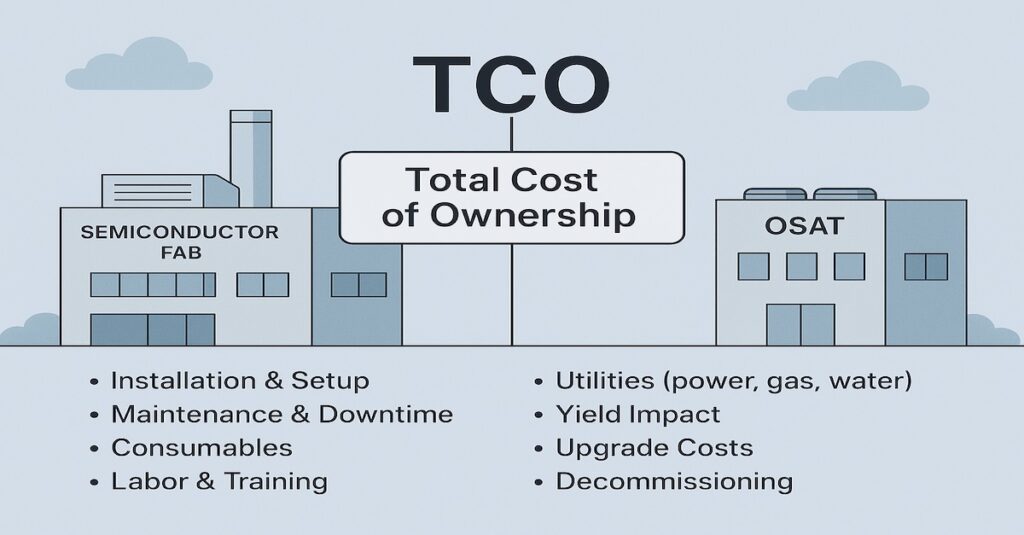

What Is Total Cost of Ownership (TCO)?

In the semiconductor industry, the cost of a tool, IP block, or software license is rarely limited to what appears on the purchase order. That figure is only the beginning of the financial story.

Total Cost of Ownership, or TCO, is a structured approach that enables companies to assess the full economic impact of acquiring, operating, and maintaining a product or service across its entire working life.

It encompasses the following:

Initial Purchase Cost: The upfront investment required to acquire the asset. This is often the most visible, yet frequently the smallest portion of the overall cost

Operational Costs: This includes recurring expenditures such as power, cleanroom real estate, workforce, license renewals, and consumables. These are day-to-day costs that quietly accumulate

Maintenance And Support: Over time, service contracts, spare parts, calibration routines, software patches, and staff training become essential to sustained performance

Downtime And Productivity Losses: Every hour of tool unavailability or design team obstruction, often caused by bugs, delays, or compatibility issues, translates directly into lost revenue and time-to-market pressure

End-of-Life Costs: When a system is retired, further investment may be required for decommissioning, migrating to newer technologies, or adapting legacy workflows

As the semiconductor business is continuously operated at the intersection of capital intensity and precision, a decision that reduces cost by a few percentage points can easily result in millions in hidden losses if it compromises reliability, throughput, or product quality.

Consider this:

- A lower-cost tester that lacks precise thermal control may undermine test integrity, leading to field reliability issues and customer dissatisfaction

- A less expensive IP block may have limited support or outdated documentation, resulting in costly silicon re-spin and substantial schedule delays

- TCO encourages a shift in thinking from a short-term view focused on cost minimization to a longer-term view centered on operational value

In the end, TCO is not just a financial metric. It is a discipline that helps teams make more efficient.

TCO In Different Parts Of The Semiconductor Business

Every segment of the semiconductor value chain, whether in fabrication, testing, design, or packaging, carries its own distinct Total Cost of Ownership profile. Each function introduces a unique set of variables that influence long-term cost. Understanding how TCO manifests across these areas is not just a matter of accounting accuracy.

Let us break it down by function:

| Segment | Initial Cost | Operational Cost | Support & Maintenance | Downtime/Hidden Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAB Equipment | Capital investment in tools like lithography, etch, deposition | Utilities, cleanroom usage, consumables like gas and chemicals | Calibration, spare parts, OEM support, software updates | Yield loss, WIP delays, throughput impact due to tool unavailability |

| Test Equipment | ATEs, handlers, probers, loadboards | Power, thermal systems, test time per unit | Socket wear, handler maintenance, debug support | Missed shipments, higher cost of quality, yield loss from mechanical issues |

| EDA Tools And IP | Tool licenses, IP block purchase fees | Compute infrastructure, integration effort | Tool support, version updates, bug fixes | Project delays, silicon re-spins due to integration/debug issues |

| Materials And Consumables | Per-unit material cost (e.g., photoresist, leadframes, substrates) | Volume-driven spend, contamination risk, rework impact | Increased tool cleaning, wear and tear | Lower yield, instability, latent defects |

| Facility And Infrastructure | HVAC, power systems, cleanroom buildout | Electricity, water, gas supply for continuous operations | Filter replacements, backup systems, emergency repairs | Production disruptions, scalability limits during expansion |

It is essential to avoid costly surprises, manage operational risk, and make informed, future-focused investment decisions. Over time, this perspective often separates companies that scale efficiently from those that struggle to contain hidden losses.

Hypothetical Examples And Mistakes To Avoid

Let us consider few hypothetical examples to explain TCO.

Example 1: To reduce capital expenses, a semiconductor firm selected a low-cost test handler for high-volume automotive lines. However, the handler underperformed thermally in production, leading to a 4 to 6 percent yield drop and multiple customer quality issues. The recovery costs far outweighed the initial savings, highlighting that long-term reliability matters more than price.

Example 2: Another company reused an older IP block to avoid new licensing fees. The IP was incompatible with the current process node and poorly documented. Integration issues went undetected, resulting in a post-silicon bug and a costly response. The delay stretched timelines and added over three million dollars in rework.

| Decision | Goal | Unseen Cost |

|---|---|---|

| Low-cost test handler | Save CapEx | Yield loss, quality issues |

| IP reuse | Avoid licensing fee | Silicon respin, delays |

| Budget EDA tool | Reduce license cost | Engineering inefficiency |

| Used fab tool | Save equipment cost | Increased downtime |

Example 3: A design team switched to a cheaper simulation tool to cut license costs. However, the tool was unstable, with slow runtimes and limited support. Engineers lost valuable time managing tool issues, leading to delays and lowered team efficiency. The short-term savings came at the cost of long-term productivity.

Example 4: A fabrication facility bought a used etch tool to reduce capital investment. While initially functional, it lacked software updates and required frequent maintenance. Uptime suffered, disrupting wafer cycle times and impacting line stability. The operational drag soon eclipsed the upfront benefit.

These cases show that decisions to save money upfront can introduce hidden costs in quality, time, and yield. TCO helps teams evaluate the full financial impact beyond the purchase price.

Integrate TCO Thinking Into Engineering And Business Decisions

TCO is more than a finance metric. It is a way of planning that must be built into engineering, procurement, and operational decisions. For engineers, this means looking beyond technical specs and considering long-term impacts such as debug effort, uptime, integration complexity, and reusability. Asking what might go wrong after deployment often reveals the fundamental cost drivers.

Procurement teams should work closely with engineering to move beyond basic quotes. They must evaluate uptime history, support terms, maintenance cycles, and parts availability. Eventually, two tools with similar specs can vary widely in lifetime cost due to serviceability and consumable usage.

| Who | Action For TCO Thinking |

|---|---|

| Engineers | Consider long-term debug, yield, and integration risks |

| Procurement | Evaluate beyond price: uptime, service, and lifecycle support |

| Business leaders | Use 3–5 year TCO models in planning and ROI analysis |

| Cross-functional teams | Share lessons learned and maintain internal TCO benchmarks |

Business leaders can use three to five-year TCO models to improve cost forecasting and ROI decisions. For example, a lower-cost tester may reduce CapEx but limit throughput, while a higher-end tool may improve unit economics in volume production. Planning with this view leads to more resilient product execution.

Finally, TCO thinking must be shared across functions. Engineering, finance, quality, and operations should jointly define benchmarks and track performance over time. Reviewing past decisions helps organizations avoid repeating costly oversights.